Mono no aware: Two Japanese Gardens

/By Kenny Fries:

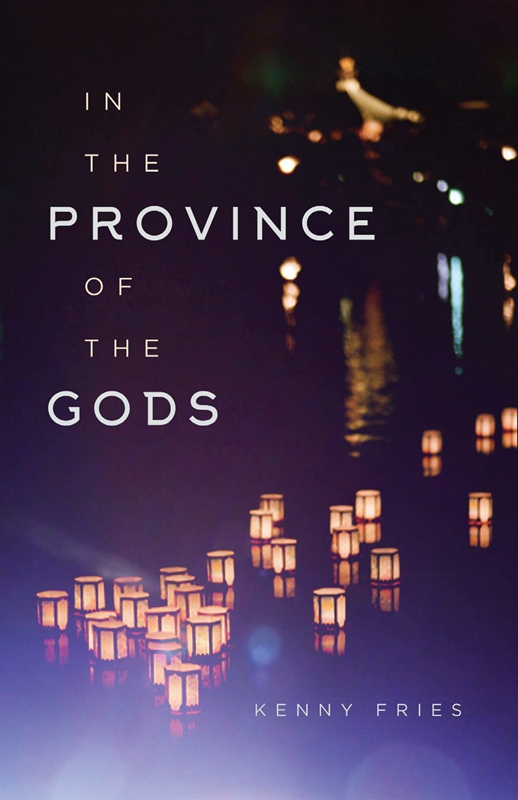

We are extremely happy to publish this excerpt from the new book In the Province of Gods by Kenny Fries, which will be launched on the 17th September at the Schwules Museum in Berlin.

To noted translator Sam Hamill, mono no aware is “a resonance found in nature. . . . a natural poignancy in the beauty of temporal things. . . . Aware originally meant simply emotion initiated by the engagement of the senses.” Ivan Morris, in his study of The Tale of Genji, says aware refers to “the emotional quality inherent in objects, people, nature, and . . . a person’s internal response to emotional aspects of the external world.” Donald Richie writes, “The awareness is highly self-conscious, and what moves me is, in part, the awareness of being moved, and the mundane quality of the things doing the moving.”

My guidebook’s photo of Kyoto’s famous garden at Ryōan-ji shows some small pebbles in three divided sections. This confuses me. Could this be a garden? It looks more like a close-up of carefully arranged spices in a kitchen cupboard.

Lafcadio Hearn, in “In a Japanese Garden,” writes:

Now, a Japanese garden is not a flower garden; neither is it made for cultivating plants. In nine cases out of ten there is nothing in it resembling a flower bed. Some gardens may contain scarcely a sprig of green; some have nothing green at all, and consist entirely of rocks and pebbles and sand. . . . In order to comprehend the beauty of a Japanese garden it is necessary to understand —or at least to learn to understand—the beauty of stones. Not of stones quarried by the hand of man, but of stones shaped by nature only. Until you can feel, and keenly feel, that stones have character, that stones have tones and values, the whole artistic meaning of a Japanese garden cannot be revealed to you.

The rock garden at Ryōan-ji is small, only thirty feet deep and seventy-eight feet wide. It consists of fifteen rocks, each of different size, color and texture, placed in five groupings, surrounded by a sea of finely raked grayish-white sand. Viewed from the veranda of the monk’s quarters, the garden is surrounded on its other three sides by a clay wall. The wall might have once been pale white, but now is light rust and contains chance patterns; over many years the wall has been stained by oil.

From no one point can all fifteen rocks be seen. No matter where one sits, only fourteen rocks, at most, can be seen at one time. I notice a group of students counting the rocks. My eyes move from the students back to the rocks, first alighting on one group, then another, and then I become fixated on the Tàpies-like pattern on the oil-stained wall.

Looking at the garden, what seems like foreground becomes background; background becomes foreground. The wall is most prominent; then one of the rock groupings, or a single rock; then focus is on the raked sand. I realize why the guidebook photo is a close-up of a tiny corner edge of the garden: it is impossible to see all at once; the experience of Ryōan-ji is cumulative.

How long have I been here sitting here, looking?

How can something so still—so permanent—be, at the same, just as evanescent?

Although many have interpreted the meaning of the garden—a representation of islands in an ocean, some famous mountains from ancient Chinese texts, a tiger chasing its cub, a symbol for the Buddhist principle of unknowing—I have not ventured to interpret the garden beyond the experience of my viewing.

I get up and walk around to the other side of the monks’ quarters. I bend down to get a closer look at the tsukubai, the stone water basin, on which there are four chiseled Japanese characters. The sign says that reading clockwise, including the hole in the middle of the water-filled basin, the characters mean, “I learn only to be contented.”

*****

The tour of Shugakuin Rikyu, on the other side of Kyoto, is in Japanese. I am the only gaijin, a foreigner, on the tour, the only person who does not understand nor speak Japanese.

Shugakuin Rikyu covers a large area; there are three levels, each with its own gardenand a distinctly different design. The two lower gardens are small and enclosed: ponds, a stream, waterfalls, stones, lanterns designed around spare wood imperial-style villas.

At the entrance to the upper garden, a path to the right rises through a hedge-covered stone stairway.

“Daijoubu desu ka? Daijoubu?”—“Are you okay? Is it okay?”—my fellow tourists keep asking me as we climb the stone path.

“Daijoubu, daijoubu, I’m okay, I’m okay” I assure them.

With the obstruction of the hedge, there is no view of the garden before ascent. However, once Rinuntei, the teahouse at the top of the stairs, is reached, the garden below—the clear pond reflecting all the garden’s pines and maple trees, another teahouse, the two bridges leading across islands to the pond’s other shore—can be seen. All of this is framed by the surrounding mountains, including the sacred Mount Hiei, not belonging to the garden but part of it, from which it is said the garden’s pond, which also reflects the mountains as well as its streams and waterfalls, is fed.

This is my first experience of shakkei, the principle of “borrowed scenery”: the surrounding landscape becomes part of the garden. This does not mean placing the garden so it has beautiful scenery nearby but actually incorporating shapes and textures of the surrounding landscape, and repeating those elements, as part of the garden itself. It is, Donald Richie writes, as if “the hand of the Japanese reaches out and enhances (appropriates) all that is most distant. Anything out there can become nature. The world is one, a seamless whole, for those who can see it.”

At Shugakuin Rikyu, the hedge that at first seemed just a hedge is still a hedge. But the placement of the hedge, its purpose, unknown at first encounter, is only revealed at the right moment, heightening the experience of revelation. The view of the entire garden is delayed for maximum impact, delayed until it can be seen as “a seamless whole.”

*****

About the book and author:

This is an excerpt adapted from In the Province of the Gods, which received the Creative Capital literature grant, and will be published in September by University of Wisconsin Press. In the Gardens of Japan, a poem sequence, was recently published by Garden Oak Press. Kenny Fries’s other books include The History of My Shoes and the Evolution of Darwin’s Theory and Body, Remember: A Memoir. He is a two-time Fulbright Scholar (Japan and Germany), was a Creative Arts Fellow of the Japan/US Friendship Commission and National Endowment for the Arts, and is a faculty member of the MFA in Creative Writing Program at Goddard College.