The Ruins

/By Ben Tufnell:

Traveling north, the vast skies, marshes and glittering lakes of Corrientes province slowly give way to endless forest. There are winding red rivers and rule-straight logging roads and, as the horizon disappears, it becomes almost impossible to orient oneself. What towns there are resemble ribbons festooned along the edges of the highways.

Here, it is said, deep in the forest, the author Horacio Quiroga (1878-1937) slowly lost his mind. Here, you are a long way from Buenos Aires or Montevideo and everything is tenuous. Life is fragile. Quiroga loved the jungle but understood that his presence there was at best contingent. In brilliant stories such as ‘Drifting’ (1912) and ‘The Dead Man’ (1920) he wrote of a constant and unceasing conflict between man and nature. He wrote of suffering, of life right at the edge of things. After his first wife committed suicide by taking poison and his second wife left him, Quiroga reportedly filled his empty swimming pool with snakes. I imagine him sitting on the veranda of the wooden house he has built with his own hands, in the middle of the forest, contemplating that febrile spectacle, a boiling, writhing mass of serpents.

Quiroga later committed suicide himself. Both his children killed themselves. These facts are like scenes from his own fiction. The river runs as red as blood, there are bird-eating spiders in the trees and there are hundreds of snakes in the swimming pool.

Travelling north, the air grows hotter and more humid. We took Ruta 12 north from Posadas to one of the most spectacular places in South America, the Iguazu Falls. The Rio Parana and the Rio Iguazu and the borders of Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay all converge here. The jungle here is improbably dense, excessively verdant, the air heavy with moisture and filled with the fluttering of masses of huge and kaleidoscopically coloured butterflies. Capuchin monkeys laugh hysterically in the forest canopy. The falls themselves are vast, overwhelmingly so. The roar of the waters is deafening.

This is Misiones province. In the seventeenth century it was one of the strongholds of the Jesuit faith in South America. At their peak the Jesuits had twelve major missions scattered across the region, each with populations in the thousands. They were eventually expelled from Argentina in 1767 and, hidden by the jungle, their cities succumbed, as all things must, to decay. Now, the very idea of the missions seems not only foolhardy but inherently doomed. The landscape ensured that the project was shadowed with failure from the very moment of its first imagining.

The biggest ruins are at San Ignacio, a few hours south of Iguazu, and they are justly famous, a must-see for any visitor to the region. Well-cleared and restored, one can wander through what must once have been a considerable town. There are the remains of many houses. There are information panels about life in the mission. And one can wander through the nave of the huge red sandstone church, now open to the sky, and admire the fig, olive, orange and lemon trees that continue to flourish amidst the crumbling stones.

But while the ruins of San Ignacio are the biggest and best maintained, a few miles south, down a red dirt track leading into the forest, we discovered a site that, although much smaller, was, in many ways, more affecting, and which seemed somehow to better illuminate the conflict between man and nature which so preoccupied Quiroga.

The Santa Luisa Mission was founded in 1633 and, alongside the Jesuit brothers, was home to some two thousand Guarani Indians. Deserted in the eighteenth century it was soon overrun by the jungle and forgotten.

This is a place in flux, where the principle of entropy is made visible. The site had been cleared, mostly, not long before our visit, and there is even a small (and empty) visitor centre, but the jungle was already reasserting itself. One of the first things we saw were the roots of a tree curling through the stones of an ancient wall and breaking it apart in imperceptible slow motion.

The site has been cleared, revealing its profound dereliction, but nothing has been reconstructed. A few fragile walls have been secured with wooden scaffolds but nothing more. And because of this it is extraordinarily evocative. The main square and the broken spine of the church are mostly clear of forest but everywhere else is doubtful. In comparison, San Ignacio seems too tidy. Santa Luisa, a ruined city in the middle of the jungle, could be a setting for a tale by Lovecraft or Borges (and of course the blind librarian was much in my mind during my travels in his country). Creepers cover every surface, gripping and pulling. There is incredible heat and humidity and a very strange kind of stillness. The forest was quiet, as if waiting.

Away from the main square everything is overgrown, is being overgrown. Santa Luisa is a place simultaneously taken from the jungle and being reclaimed by the jungle. The cracks widen. Huge flowers bloom, briefly. Things are drifting back into the entropic zone. It is impossible to tell where the old Jesuit mission ends and the jungle begins. I didn’t – couldn’t – go far enough into the undergrowth to determine that precise border. Thick spider’s webs were stretched between the trees and I turned back when I noticed the husks of some huge and grotesque looking insects, as big as my hands, clinging to the underside of a branch that barred my passage.

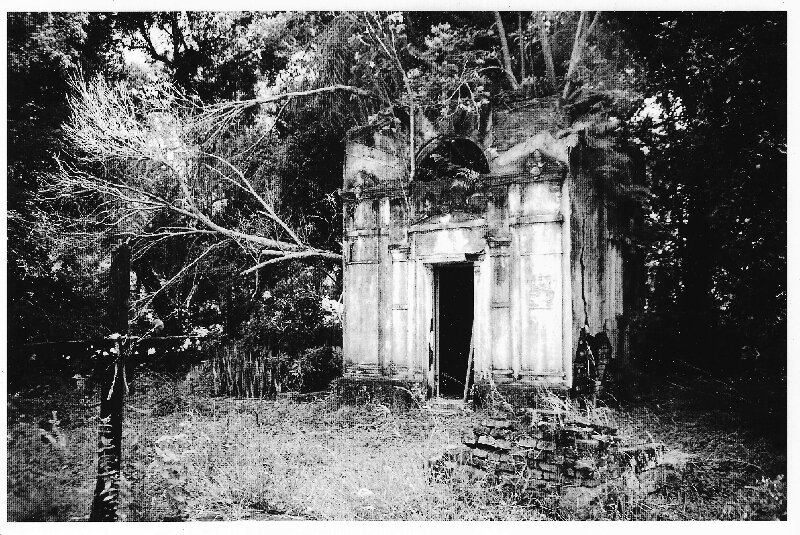

The old cemetery is the eeriest part of the site. The locals continued to use it until the 1960s and it is dense with graves, tombs, and even grand crypts, all now derelict. Dragon’s Teeth forces up through the graves. The once ornate tombs are broken open. The beautiful ironwork and stone carvings are now embellished with gripping tendrils of the very foliage they were meant to imitate. A steady humming of insects fills the air. Wasps nest in crypts filled with impenetrable shadows and dusted webs. Broken coffins are glimpsed through the wrought gates of the big family mausoleums, the heavy wooden doors long since rotted away. Flowers, creepers, vines cover every wall. Even in the bright sunlight, it is an unnerving spectacle. An old skull, missing its jawbone, dislodged by the ongoing collapse, had rolled from one decrepit sanctuary and lay in my path.

I wondered what it must have been like for the priests, their pale European skin blistered by the unceasing glare of the sun. How did they cope with the always encroaching darkness of the forest, the spiders and snakes concealed within every shadow, the overwhelming heat and humidity? How did they keep faith when His work seemed to be constantly undoing their best efforts?

It was clear to me that if the caretakers stopped maintaining the square and the broken church, it would be only moments before the jungle completely enclosed and obliterated the site, breaking down the ruins and pulling them back into the red earth.

We were not there long. We looked around together and then I wandered off to the edge of the site, where it was difficult to tell if I was still in the site. When I looked back I saw that C had crossed the square and was making her way back down the track towards the car. She passed out of sight and I was alone. There was silence. Or rather there wasn’t silence, for the forest is always busy, but there was a focussing. I became overwhelmed by my thoughts; I was aware of simultaneous registers of time (a sensation not unlike a fissure opening at what Robert Smithson once called ‘the cracking limits of the brain’). Undoubtedly, I was affected by the heat, the long drive, the ruination, the tropical Gothic of the cemetery, the pool of snakes, the blood red river, the huge waterfalls and the vast whirlpool that lies at their base. Standing there, a few minutes seemed to stretch like hours, years. I felt I could almost see the forest creeping forward, tightening its grip on the shattered brickwork, bright flowers like fresh wounds blooming and fading.

I saw that I was looking down into an open tomb. The sunlight at my back was so bright and the contrast with the inky darkness inside so extreme that there was an astonishing contrast, so that the shadows within that grim enclosure seemed to be solid. And I had the idea that I was looking through a point, a punctum, in its surface. I thought then of the Aleph, described by Carlos Argentino in Borges’s account as ‘the only place on earth where all places are -- seen from every angle, each standing clear, without any confusion or blending…’ For it seemed to me I could then see before me the unfolding of this place over time, from primordial swamp, filled with ferns, mosses and small crawling things, to the gradual encroachment of the forest and the eventual arrival of the missionaries (I saw their terrified passage deep into the unknown interior of dessicated deserts, fugal marshes and evil forests) and even the birth and death of the lizards, insects and trees, all those things that were here and now.

The Aleph was not an opening. Carlos Argentino himself described it as ‘a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brilliance.’ He attempted the impossible task of writing down what he saw:

‘At first I thought it was revolving; then I realised that this movement was an illusion created by the dizzying world it bounded. The Aleph's diameter was probably little more than an inch, but all space was there, actual and undiminished. Each thing (a mirror's face, let us say) was infinite things, since I distinctly saw it from every angle of the universe.’

This mysterious object was located in the basement of an old house in Garay Street in Buenos Aires, now long vanished. We had been there, of course, and to Borges’s house too, hoping to discover some vague trace but finding, inevitably, nothing.

But now, in the jungle amidst the ruins, staring into that dark tomb, I had, just for the most fleeting moment, a glimpse of the Aleph (or of a kind of Aleph, for Borges himself said that he thought the one in Buenos Aires was a false one, and that there might be many). It was gone as soon as it was present. And then the darkness was only darkness again. I walked slowly onwards, wading through a warm viscous liquid: time itself. I saw human activity, the jungle, each assimilating the other again and again, not erasing the past but absorbing it. Endless and infinite cycles.

Something large moved in the forest. I had the weird notion that if I saw what it was, my reason would give way, would crack; for I fully expected a great and ancient lizard to come lumbering out of the undergrowth. Shuddering, I quickly made my way back through the trees to the main square, where the full sun had now attained an infernal intensity. Huge birds (or were they pterodactyls?) flapped wearily into the sky from the tops of some of the trees. I passed through the crumbling gateway and down the dirt track, past the empty information centre and back to the car, where C was waiting. Behind me the whole site shimmered in the heat, like a reflection in oil, unsteady. Already I was wondering if I had dreamt it.

I started the car in silence, drove us back along the track onto Ruta 12, and we headed north.

***

Ben Tufnell is a curator and writer based in London. He has published widely on modern and contemporary art with a particular focus on art forms that engage with landscape and the environment. His most recent book is In Land: Writings About Land Art And Its Legacies (Zero Books, 2019).