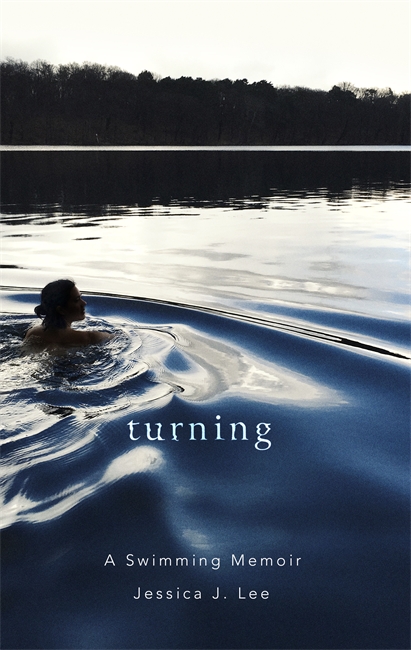

Swimming in the city and country: Turning - by Jessica J. Lee

/IMAGE: Katrin Schönig

Read by Paul Scraton:

Early on in the pages of Turning, a swimming memoir about taking a dip in 52 lakes in Berlin and the surrounding Brandenburg countryside, Jessica J. Lee admits to fears and insecurities in the water. This is something I share. I have never been a massive fan of swimming, whether in the sea or the swimming pool, and especially when out of my depth. It has only been in the past couple of years, swimming in some of the very same lakes that Lee visits in this excellent book, that I began to conquer those fears.

It was then that I began to understand what people were talking about when they - like Lee herself - quoted Roger Deakin and his description of the ‘frog’s eye view’. As Lee describes being in the water in Brandenburg, surrounded by the pines and the sky, I can picture it exactly as I have experienced it as well. You do get a different view from the water, a different understanding of place. And that, for me at least, is ultimately the story of this book: as well as personal history sensitively and bravely told, Turning is about a person gaining a feeling for the history and the stories of the places she visits, deepening her knowledge of the geology, ecology, communities and political history of the city she lives in and the surrounding countryside, each time she takes to the water.

As someone who both shares these interests about place in general, and about Berlin and Brandenburg specifically, it is not surprising that I found myself nodding in agreement and recognition as I read. There were other elements of the story that resonated as well: the loneliness of being new in a big city and of building a personal connection to the place by getting to know and to love the landscape, the forests, the suburban S-Bahn lines and the gruff owners of rural snack kiosks.

Lee is an elegant writer; precise in her description, thoughtful in her observation, and most of all interested in the world that surrounds her. This is not always the case when it comes to memoirs, which can sometimes become so tied up in the internal emotions of the writer that there is no space for any exterior, for the world around them, and therefore context to the story they are trying to tell. In Turning, Lee’s personal journey is deeper and richer for the reader because the lakes and their surroundings are characters in the story. As is the weather. As are the seasons. The plan was to explore the 52 lakes over the course of a year, and so Lee was swimming at the height of summer and in the depths of the winter, breaking the ice with a little hammer in order to clear enough room for her to have a swim.

Indeed, one of my favourite lines in the book - one that had me reaching for a pen in order to scribble it down for later - concerned the shifting of the seasons: “It’s all too easy,” Lee writes, “to be sucked under by sadness in the autumn.” I understand that emotion only too well, even if I haven’t (yet) tried a plunge in an autumnal pool to try and alleviate the October blues.

And then, a few pages later, more recognition: “I’ve become divided, stretched across places.” At the very time I was reading this book, I was working on my own project about walking the outskirts of Berlin. One of the motivations for these walks was to try and gain a better understanding of the city I live in a time when my feelings about place, belonging and identity had been thrown into turmoil by referendum results and a series of trips “home” that made me wonder, more than I ever had before, where “home” actually is. I too have felt stretched and divided. The only question, is whether it matters. Each walk, each swim, can help the clarification process.

Walking or swimming. Building our connection and understanding of a place by interacting with the landscape, the history and the people, can be done in different ways. The strength of the book is, I believe, that it not only is a good story very well told, but that it will make readers think about their own places, their own feelings of home and belonging, of their own lakes, forests or city streets, and think a little deeper about them. Jessica J. Lee’s is a trip to the lake well worth taking, inspiring even this reluctant swimmer to reach for his swimming shorts (if not the ice hammer).

Support your local bookshop! Go and get your copy of Turning by Jessica J. Lee there. Meanwhile, here is Jessica's website.