We continue our series of occasional short interviews with contributors and friends of Elsewhere with five questions for JLM Morton, who we featured in our Trespass issue.

What does home mean to you?

Home, in it’s very truest sense, is the place where I grew up – Cirencester, a market town in Gloucestershire where I wore a groove into the street I lived on, going back and forth to the parks at either end of the street: the now paywalled Bathurst Estate park and the municipal Abbey Grounds with its sweeping cedar tree, elderly mulberry, a lake full of pike that my brother used to catch and the old cold store that looks like an egg cupped by a mound of grass. I couldn’t live there now – there are aspects of the place that I can only stomach in small doses (like a toxic family member) – the showy Cotswold privilege and snobbery, the loafers and chinos, small town social dynamics, the town/gown antagonism with the Royal Agricultural University that led to many a fight in the marketplace on a Saturday night when I was younger. I suppose I found home in the out-of-the-way quiet places, in the ‘maze’ we built as kids in the thicket at the back of the school field, in the den we claimed on the dirt hill at the edge of the car park, in the copse where I snuck out at dawn with a friend to set a fire and fry an egg in the skillet I’d smuggled from our kitchen in a rucksack. Home was also the rivers and brooks that run through the town and in and out of both parks, where I paddled, as well as the open-air pool where I seemed to spend entire summers diving off the board and burning my tongue on too-hot chocolate in plastic cups from the tuck shop. Now, wherever I go in the world, water feels like home to me – I can sit and be with water for hours and never get restless.

Which place do you have a special connection to?

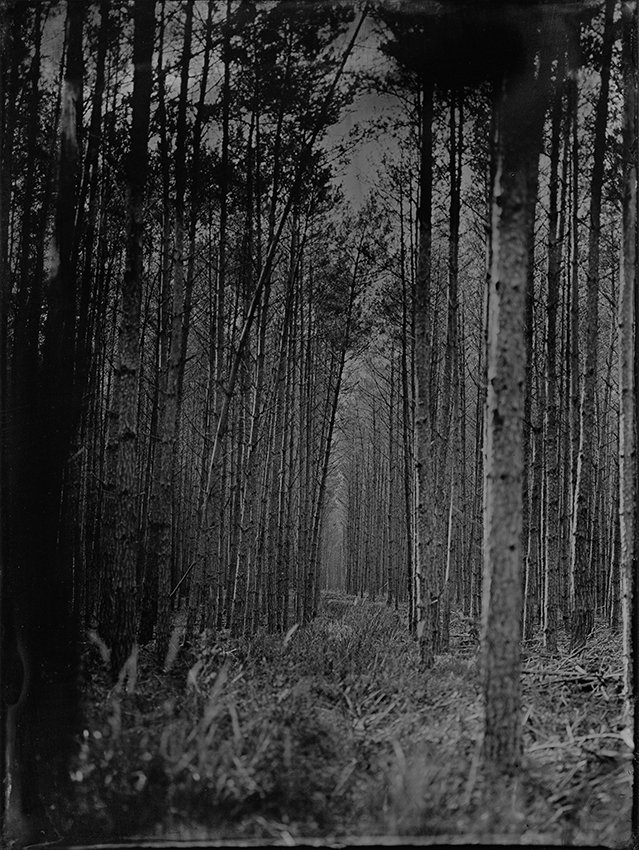

I feel a very special connection to West Africa, a region I spent a lot of time living and working in during the early 2000s and 2010s. I have a background in education, particularly supporting girls and children with disabilities to access school which took me to various places including Nigeria, Benin Republic, Ghana, Togo, Cameroon. I feel a very particular affinity with Sierra Leone – there is something about the people, the colleagues I’ve worked with over the years, that I love and admire. It’s something like resilience but not – everyone I’ve ever met there has always welcomed me with open arms, with a kind of high-spirited joy, a no-f*cks-left-to-give attitude that carries them along and which I find inspiring. I first went there in 2003 just after the civil war ended to work with the Forum of African Women Educationalists. Though excluded from public decision making, what women have done to create nonpartisan community dialogue to advance peace has been extraordinary. The majestic cotton tree that stands in the oldest part of Freetown is the most on-point manifestation of this attitude – associated with the founding of the capital by a group of formerly enslaved African Americans, known as the Black Nova Scotians, who gathered under its shade to pray and celebrate their freedom, the tree is a landmark, revered by the local community for its spirit and historical importance. Sierra Leone is an extraordinarily beautiful country – I especially love the area around Kenema, where the trees look like gods and the forest is all you can see for miles.

What is beyond your front door?

Immediately beyond my front door is a street full of families and elderly folk, rows of houses built on an orchard in the mid-1950s where the springs along the hill still seep up through the kerbsides. Some of the residents have lived here since these houses were built. Beyond our gardens is the A46 road down to Bath. To the back is a steep climb up to Rodborough Common. To the front, over the rooves, Selsley common and a view towards the Severn Vale where the land flattens and on a good day you can see the Forest of Dean beyond the river.

What place would you most like to visit?

I have always wanted to go to Rajasthan, lured in part by the textiles, beadwork and jewellery as well as the desert. I’m really fascinated by the ways women all over the world have used weaving and making as a kind of language that speaks beyond the confines of the written word. It’s a way of transcending boundaries and telling stories that express culture and history which I feel deeply connected to. I come from a long line of textile workers – something I only discovered recently and which explains why I have boxes full of textiles that I’ve collected from around the world that I really have no space for at all but can’t let go.

What are you reading / watching / listening to / looking at right now?

I’ve been collaborating with the brilliant comic Emma Kernahan and composer Mara Simspon on Lost Mythos, a show that blends the unruly folklore of old, weird Albion and stories from modern rural life, simultaneously embodying and exploring ancient archetypes and questioning our yearning for them. Mara has written a beautiful album, Living Matter, in response to my poems and I’ve got that on repeat. She also did a brilliant playlist ‘Humans in the Room’ for 6Music’s Freakzone which I highly recommend banging on.

I always have multiple reads on the go and my tbr pile is ridiculous. I’ve just finished Isabelle Baafi’s collection Chaotic Good which was thrilling to read – innovations in form and one of those books that make you feel like you’re being let in on a secret that only you will know. I’m now reading Michael Symmonds Roberts’ brilliant and moving memoir Quartet for the End of Time which is about grief and the premiere of Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps to a crowd of Jewish prisoners of war in a deathcamp and its legacy – it feels remarkably prescient. I have also got Jen Calleja’s demented and revelatory Goblinhood on the go, a series of encyclopaedic essays and poems on her theory of goblins in pop culture. I can’t describe it, you have to read it. I’m writing about pilgrimage at the moment, so I’m reading Esther de Waal’s The Celtic Way of Prayer too which is about inner and outer journeying, poetry and prayer / poetry as prayer.

I’ve just binged Narrow Road to the Deep North on BBC iPlayer. Lured in by the love story, I got sideswiped by the turn into the horrors of the Death Railway built by Asian labourers and Allied POWs to connect Thailand with Myanmar, but I thought this was an utterly brilliant drama, one of those ones I can't stop thinking about. I realise I’m being drawn to war stories right now, no doubt looking for answers to our current predicaments. Original novel by Richard Flanagan, the only writer to have won both the Booker and the Baillie Gifford. The way he / the director handle the subtleties of emotion really blew me away. Incredible storytelling.

I keep meaning to get up to that London to see the Ithell Colquhoun show at Tate Britain. Painter, occultist and poet, Colquhoun is getting a long-overdue reassessment. She reminds me a lot of Monica Sjöö, a radical anarcho ecofeminist who played a pivotal role in the peace and women’s movements of the 1970s and beyond. She got her own retrospective in 2023 at Modern Art Oxford and at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. Both of these artist remind us that we are not simply one and the other, goddess and god, male and female. Our boundaries are permeable, all matter is vibrant and that nothing comes from nothing, our differences are joyously multiple at many levels and scales. Such is the fecundity and variousness of our planet – that recognising our relationality and radical inter-connectedness, not focusing on our oppositions, is a form of resistance. A callback from the past, a reminder we need now more than ever.

JLM Morton is a writer, celebrant and community arts producer from Gloucestershire in the west of England. Her poetry has featured on BBC6 Music and appeared in Poetry Review, Poetry London, Rialto, Magma, Mslexia, The London Magazine, Anthropocene, The Sunday Telegraph and elsewhere. Her prose writing has won the Laurie Lee Prize, been longlisted for the Nan Shepherd prize and extracts from Tenderfoot have been published in Caught by the River, Oxford Review of Books and Elsewhere: A Journal of Place. Juliette is the winner of the Geoffrey Dearmer and Poetry Archive Worldview Prizes and she is a Pushcart Prize nominee. Her debut poetry collection Red Handed, was highly commended by the Forward Prizes and a Poetry Society Book of the Year (Broken Sleep Books, 2024). www.jlmmorton.com

You can read ‘Over, Across’ by JLM Morton here.