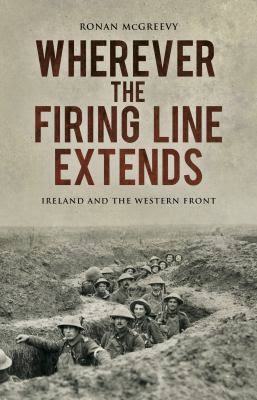

The Library: Wherever the Firing Line Extends - Ireland and the Western Front, by Ronan McGreevy

/Read by Marcel Krueger:

One of the interior decoration staples of many an Irish pub, or really any self-proclaimed 'quirky' beerhouse between Norway and Sardinia is the 'On this site in 1856 (or 1768 or 1699) nothing happened'-sign. There is no statement more untrue. Even though the events that took place near the sign over the last centuries may have gone mostly unrecorded in written or oral history, it does not mean that all the love stories, tragedies, atrocities that occurred there have never happened. For this exact reason, I am an advocate of memorials, regardless if they are large Victorian stone slabs in public parks, small blue plaques on buildings or even smaller, unobtrusive ones like the German Stolpersteine dedicated to the memory of Holocaust victims or the Last Address plaques in Moscow remembering the victims of Stalin's purges in the 1930s. All these memorials and monuments help us to view both the past and the present in context, to provide details and names of happenings long ago that we would have otherwise passed by without thought.

Ronan McGreevy has done a similar thing in his book: through a framework of site-specific memorials, all accessible today throughout southern Belgium, the north of France and Germany, he paints a picture of the actions of Irish troops on the western front in World War I. Beginning with the first shots fired at Casteau in Belgium to, incidentally, one of the last 1918 actions near Mons (where a marble plaque remembers the 5th Royal Irish Lancers) just 12 kilometres from that first engagement. Printed in hardcover and enhanced with black-and-white and colour images as well as maps for most chapters, the book is structured along both the British troop movements and the memorials that came after. Some chapters focus on specific military actions and the units involved, like the railway station at Le Pilly and the 2nd Royal Irish Regiment; others focus on single soldiers, like poet Francis Ledwidge (remembered by a plaque from 1998 near Passchendaele) or Robert Armstrong, a World War I veteran who became the head gardener of the Valenciennes military cemetery after the war and who died in a German prison camp in 1944. One story and chapter that stood out for me is the story of the Iron 12, twelve Irish prisoners executed by the Germans after being caught hiding with Belgian civilians.

Despite that fragmented approach, the book manages to provide an excellent overview of the Irish involvement in the British campaign 1914 - 1918 in contrast with the Easter Rising in 1916 and republicanism at home. As McGreevy puts it in the introduction: 'It is perhaps the great paradox of Irish history that more Irishmen died fighting for the Crown than ever died fighting against it.' Sometimes the fragmentation of the chapters however seems to lead McGreevy slightly astray, and in just a few paragraphs we cover decades and move from the detailed description of an action on the ground over to events in Ireland many years later and just barely find our way back to the actions on the western front. Also, due to the wealth of details presented in here the book will mainly appeal to amateur historians and other World War I enthusiasts.

And yet the strength is the concrete interface of occurrence and memory expressed as memorials, and their connection with the landscape. The writing is strongest when McGreevy explores the sometimes hidden or unobtrusive location of the memorials and their equally unobtrusive history and changing political significance, from the small plaque at Mouse Trap Farm to the large Island of Ireland Peace Park in Messines, opened by Irish president Mary McAleese, Queen Elizabeth II and Belgian King Albert II in 1998.

'Wherever the Firing Line Extends' can be used as guide book on the ground, and at the same time is a fine addition to the canon of publications on the double identity of the Irish soldiers in World War I. While the book is focusing on individual stories in the face of industrial scale slaughter, it is the new approach of appreciating the memorials later generations left for these men that makes it a refreshing read. After all it is for us, the living, that these memorials exist. They remind us not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

About the reviewer: Marcel Krueger is a writer, translator, and editor, and mainly writes non-fiction about places, their history, and the journeys in between. His articles and essays have been published in the Daily Telegraph, the Guardian, Slow Travel Berlin, the Matador Network, and CNN Travel, amongst others. He has translated Wolfgang Borchert and Jörg Fauser into English, and his latest book Babushka's Journey - The Dark Road to Stalin's Wartime Camps will be published by I.B. Tauris in 2017.