Out of Place No.04: 'The Summer Book' by Tove Jansson

/Out of Place is an irregular series about movement and place, and the novels that take us elsewhere, by regular contributor Anna Evans.

‘Floating on the water like a drifting leaf.’ – Islands and imaginary worlds in Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book.

The sea is always subject to unusual events; things drift in or run aground or shift in the night when the wind changes, and keeping track of all this takes experience, imagination, and unflagging watchfulness.

In a cabin on an island somewhere in the Gulf of Finland, a little girl awakes under a full moon to find herself alone in bed. Perhaps it is the moonlight that illuminates and sweeps across the island to wake her, like the sea covered by ice at its shores. She remembers that she is sleeping in a bed by herself on the island because her mother is dead. She climbs out of bed and looks out of the window. It is April, and the floor is very cold under her feet. The fire is lit and flames flicker on the ceiling. The black ice on the sea mingles with reflections of the room, and its furniture and objects. It appears as if the suitcases and trunks that are lying open on the floor are filled with moss and snow, and ‘coal-black shadow’. There is a dreamlike intensity to the images and reflections that she sees, a mingling of perspectives of inside and outside, so that we are not sure if she is awake or dreaming. She watches their luggage float out in a river of moonlight, ‘All the suitcases were open and full of darkness and moss, and none of them ever came back.’ As she drifts back to sleep, Sophia lets the whole island float out on the ice and on to the horizon, as if she is letting go.

The Summer Book is full of such moments of space and solitude. Ali Smith writes that ‘the novel reads like looking through clear water and seeing, suddenly, the depth.’ The presence of water is a constant and the book is full of images of floating and drifting, sinking and diving. For the inhabitants of an island, the sea is always there, ‘a long blue landscape of vanishing waves,’ an immersion in water. The book contains beautiful and striking descriptions of the sea and the archipelago, such as the arrival of a storm, when the island begins to look small and insignificant and the sea becomes immense, ‘white and yellow and grey and horizonless’.

Tove Jansson, known mainly as creator of the Moomins, was a writer, illustrator, and painter, who wrote several novels and short stories for adults including The Summer Book, published in 1972. Running through the book is the relationship between a grandmother and granddaughter, and their shifting perspectives, which Jansson navigates with a light touch. They are companions who explore and have adventures together, arguing and playing together during a summer on the island. Recurring throughout are their thoughts and conversations which touch on questions about life and death in a way that is open-minded and truthful, irreverent, and unconventional.

There is a sense of displacement and loss that comes from those images of the suitcases gliding away, the black ice and the moonlight, reflections of the darkness outside and the fire inside. This moment of grief is never dealt with explicitly, but perhaps a sense of loss hovers at the edges of the narrative. Jansson wrote The Summer Book after her mother’s death and in some ways the book feels like a remembrance of absent friends, and of an intense spirit of creativity and imagination which seems emblematic of her art and personal relationships. Contained within its pages is a deeply held belief in difference and free thinking, and a tolerance for others. It is a book about age and wisdom – ‘you have to come to it by yourself’ - that manages to be both weighty and understated, philosophical and poetic, moving and very funny.

It is a book that resists characterisation and one that creates space for the reader through its structure: a series of vignettes, of connecting episodes and stories that are interlinked and overlapping. Ali Smith describes how the ‘profound quiet of the setting’ allows space for all the things left unsaid to be heard. ‘Jansson's brilliance is to create a narrative that seems, at least, to have no forward motion, to exist in lit moments, gleaming dark moments, like lights on a string, each chapter its own beautifully constructed, random-seeming, complete story.’

It is a book that rewards re-reading, one of those books in which you notice different things each time you read. Reminding me of a time when I sat down to write, with the book beside me, in the early mornings of a long dark winter. I would set an alarm for 5am and sit with a blanket around me, often lighting a candle, and write for an hour or two when daily life would start to intrude again; the rituals of getting ready for school and work. The flame of the candle was the space I was carving out for myself, and sometimes a glimmer of an idea would surface. Writing back through the lens of memories real and imagined, I started to realize that it was places I was seeking to capture in words, a particular kind of longing.

The Summer Book is rich in place with a deep respect for the natural landscape. The setting is a tiny rocky island in the Pellinge archipelago in the Gulf of Finland. Tove and her brother Lars built a house on the island of Bredskär in 1947, and Tove and her long-term partner Tuulikki Pietilä spent many years together on a nearby island Klovharun further out on the rim of the archipelago, where it is possible to visit their summer cottage. The book is set during a summer, or perhaps a series of summers spent on the island: ‘It was just the same long summer, always, and everything lived and grew at its own pace.’ For me, Tove’s writing, and her descriptions of the island, render a landscape I recognize from summers spent in Sweden as a child, the forests, lakes and archipelagos, the moss and granite rocks. The vividness of that landscape for me feels like the experience of summer, a place I associate with space and light.

The book describes how these tiny rocky islands are remarkably resilient and self-contained. A small island ‘takes care of itself. It drinks melting snow and spring rain and, finally, dew, and if there is a drought the island waits for the next summer and grows its flowers then instead. The flowers are used to it and wait quietly in their roots.’ The human inhabitants of the island are self-sufficient too and the book is full of reflections on island living and island dwellers. In her foreword to The Summer Book, Esther Freud describes her visit to the island and how amazed she is to find how tiny it really is. She marvels at the use Jansson made of her surroundings ‘investing so much detail in every patch of ground’. Here, she thinks, was a writer who understood ‘the proper magnitudes of our small worlds’.

Although its setting is a tiny island, it is a book that is full of travel and imaginary worlds. When a picture postcard of Venice arrives one day, Grandmother begins to recall her travels in Venice and Sophia is curious about this city built on the water. Tove herself loved to travel and had spent time in Italy. The postcard is ‘the prettiest picture anyone in the family had ever seen. There was a long row of pink and gilded palaces rising from a dark waterway that mirrored the lanterns on several slim gondolas. The full moon was shining on a dark blue sky, and a beautiful, lonely woman stood on a little bridge with one had covering her eyes.’ The image of Venice sinking into the sea fuels their imaginations and they build their own pretend version of Venice, carefully constructing palazzos and bridges and gondolas: ‘There is something very elegant about throwing the plates out the window after dinner, and about living in a house that is slowly sinking to its doom.’

For Grandmother, moments of stillness and of careful observation are meaningful. She observes with care a blade of grass, a fragment of seabird down, becoming entranced by tiny details - the way they are constructed, how they move in a draft of air. This attentiveness to details can be revelatory, and Grandmother knows that she must give these moments her full attention: ‘It was important for her not to stand up too quickly, so she had time to watch the blade of grass just as the down left its hold and was borne away in a light morning breeze. It was carried out of her field of vision, and when she got on her feet the landscape had grown smaller.’ A tiny piece of driftwood, a scrap of bark that she finds on the shores of the island, could become a whole world. ‘If you looked at it for a long time it grew and became a very ancient mountain. The upper side had craters and excavations that looked like whirlpools.’

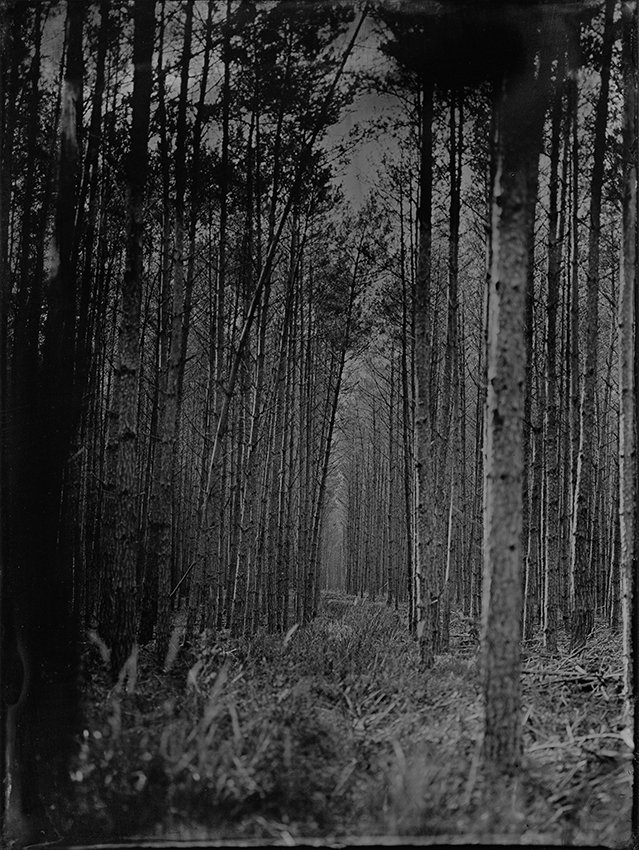

Running through the book is a deep awareness and respect for the living creatures they share the landscape with, for every plant, insect, bird, and animal that dwells on the island. The magic forest is a ‘dense, sheltering wall of trees’ that ‘had shaped itself with slow and laborious care, and the balance between survival and extinction was so delicate that even the smallest change was unthinkable.’ They leave the trees untouched, for to clear a space between them or attempt to separate them ‘might lead to the ruin of the magic forest’. Grandmother sits in the magic forest and carves animals from driftwood that she finds: ‘They retained their wooden souls, and the curve of their backs and legs had the enigmatic shape of growth itself and remained a part of the decaying forest.’ As for the forest, left to themselves, ‘the trees slipped deeper and deeper into each other’s arms as time went by.’

This sense of preservation and letting things be is part of their existence on the island, to leave parts untouched, to not leave too many traces. They are part of a bigger system, a sustainable island environment in which you sense that all things are equal and have their place. The human inhabitants of the island stick to narrow paths by which they wander the different parts of the island, the rocks and to the sand beach, bypassing the carpet of moss and being careful not to step on the frail moss: ‘Step on it once and it rises the next time it rains. The second time, it doesn’t rise back up. And the third time you step on the moss, it dies.’ Their habitation of the island is based on a deep understanding and reverence for the other forms of life with which they co-habit.

‘The Tent’ is an incredibly beautiful and moving section of the book, in which the story seems to echo through the dual perspectives of grandmother and granddaughter. Sophia wants to hear Grandmother’s stories about the past and about her days as a Scout leader, and what it was like to camp outside in a tent. But when Grandmother tries to put her memories into words, they feel fragile and distant; it is as if everything is gliding away from her. Sophia sets out to spend the night in a tent, and as she sets out on her adventure, the creek where the tent is placed starts to feel like a ravine, distant and forsaken. She zips up the little yellow tent which feels small and friendly, ‘a cocoon of light and silence’. In the long summer evenings, it is still light outside, and she falls asleep. Later, waking up in the night, she finds that darkness has entered the tent and now surrounds her. She can hear strange movements and sounds, ‘the kind no one can trace or account for’. In this darkness she finds she really listens for the first time in her life and notices the feel of the ground under her feet which is ‘cold, grainy, terribly complicated’. In this awareness and surrounded by darkness she has the sense that the island has grown tiny, that it is ‘floating on the water like a drifting leaf’. Returning to find Grandmother awake, Sophia begins to tell, in her own words, what it feels like to sleep in a tent.

As the summer nights begin to fade away, the human inhabitants begin to remove their marks and traces from the island, ‘a place for everything and everything in its place’. Grandmother feels the island becoming cleaner and returning to its original condition. It begins to feel lonelier and more distant and secret. There is a sense of taking leave, as Grandmother sits by the water at nightfall, watching the passing boats. The Summer Book is full of such quiet moments, where the lightness of Tove’s writing reveals depths.

***

Anna Evans is a writer from Huddersfield who lives in Cambridge, with interests in place, memory, literature, migration, and travel. She enjoys writing about landscape – nature, cities, and all the places in-between. You can read more about Anna and her work on her website The Street Walks In. You can find more of Anna’s contributions to Elsewhere here.