Capturing the forest – the photography of Eymelt Sehmer

/By Paul Scraton:

It was a cold winter day when Eymelt invited us to her studio in Berlin-Weißensee. She had been looking for models, people she could photograph using a technique that dates back to the earliest days of photography. It would take a while, she said, to capture each image. We would – in this era of mobile phones and Instagram, when more photographs are taken in a single year than in the previous century – have to be patient.

The collodion wet plate process requires that a black tin plate be coated, sensitized, exposed and developed in the space of about fifteen minutes. We spent a few happy hours in her studio room, laughing and joking and mainly talking to Eymelt’s legs, because she was usually under a thick blanket of some short, either behind the camera or in her self-made dark room where she prepared the collodion emulsion, coating the plates and then developing them by hand.

‘Did you ever try this outside?’ someone asked, and in those six words, an idea was born.

In early 2017, Eymelt had made a short film based on my book Ghosts on Shore about the Baltic coast, and we had been keen to work together on a project again. The idea of finding a way to take the collodion wet plate technique out of the studio and into the landscape was the starting point for what would become our new book.

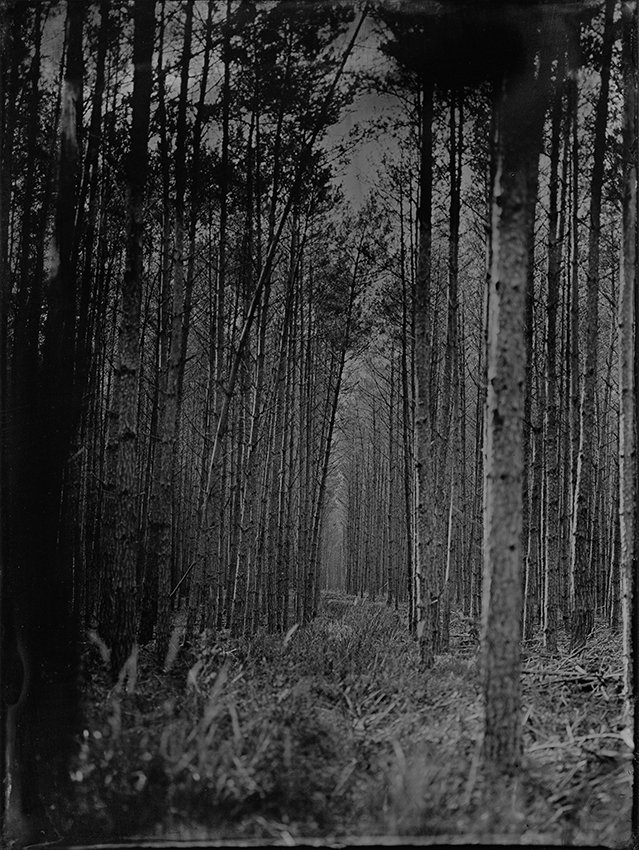

In the Pines is a combination of words and images. It is my novella, a whole-life story told through fragments about a narrator’s relationship to the forest, sharing the pages with Eymelt’s photographs from between the trees. Some of the stories contained within the book gave Eymelt inspiration when she took her mobile darkroom into the forest. Some of the images she returned to inspired new stories in turn. Eymelt’s art both illustrates the text and inspires it, and I know I would have created something different, something lesser, without our collaboration.

To celebrate the launch of the book this autumn I wanted to celebrate Eymelt’s talent and her art. What follows is my short interview with Eymelt, about the photography in our book and what she’s planning next.

What is it about this technique that is so appealing to you as a photographer?

First, I love analogue photography in general. And then, what I find most intriguing about the collodion wet plate process, are the imperfections of the images. The photos are blurred; the images look liquid, creating blind spots. These are voids to be filled by the viewer’s imagination. And each photograph is truly unique.

When you first showed me the technique in the studio, it seemed almost impossible you could take it outside. What specific challenges did you face when taking your camera out into the forest?

The most challenging thing involves the developing, in that I have to do it immediately. The coated photoplate needs to still be wet for the developing process, which means I have about ten to fifteen minutes from coating the plate until developing it. I have to therefore coat each plate by hand before each photograph. I cannot prepare a batch in advance.

Once the photograph is taken, the plates can only be handled in darkness. So I need a mobile darkroom, and I built one out of a former steamer trunk. Transporting this monster out into the woods, to basically build a lab out there among the trees, was quite a challenge and was time-consuming as well.

Added to all this, and related to how much time everything takes, is that I am somewhat exposed. To the weather, and especially the temperature, which can have a major impact. During the winter, for example, the chemicals on the plates froze, creating some beautiful crystalline structures on the photographs. It was as if the environment had engrained itself on the image. But that is also what I love about the technique – you have to embrace the uncontrollable and see what happens.

In my introduction, I’ve written about how the photographs both related to the text and sometimes also inspired it. How was it for you, working on a collaborative project like this?

Generally, the inspiration for my works comes from fairy tales and myths, so the starting point is almost always a story. In the Pines was my first ever collaboration of words and photography, and as your language is very evocative, I could picture some of the images in my head right away. What also helped were the walks and talks we had, especially through the landscape. It helped me get a feeling for it.

Text is interesting because it can go into detail, and you take the reader with you. With an image it is slightly different. I am choosing the frame of course, the perspective and the light situation. But there is more there for the viewer to decide for themselves. Not least when it comes to how close or carefully they decide to look.

My favourite aspect of the collaboration was that it basically forced me to take the technique outside and into the woods. Without this project, I’m not sure I would have given it a try. And spending all that time out there with my camera and my mobile darkroom meant I had lots of beautiful encounters with mushroom foragers, kindergarten kids, horses and hikers.

So will you be taking more landscape or outside photographs using this technique in the future?

I’m certainly going to take some more. I would also like to experiment more, try some things with filters etc.

In the Pines is all about the narrator’s lifelong connection to the forest. What does the forest mean to you?

For me the forest has always been, since early childhood, a kind of retreat – a place of sanctuary. I could lose myself in fairy tales, and in difficult emotional times it was a place where I took refuge. To this day, the forest is still a place of solace for me.

It was also an adventurous playground for myself and my brothers. A place where you could pick berries and hunt mushrooms, where you could climb trees and build secret hiding places far from the parents’ eyes. It was our own microcosmic realm and it captivated our imagination.

Finally, what’s next for Eymelt Sehmer? You have a gallery in Berlin – are there any projects or news from the gallery you’d like to share with us?

Oh, I have lots of ideas! In early 2020 I took the Trans-Siberian Express through Russia to Mongolia where, thanks to the pandemic, I got stuck. Initially I’d intended travelling there to take photographs of the Dukha people, a nomadic reindeer tribe, and then, having got stuck in Ulaanbaatar with my guide and his family, I met his wife Mugi’s motorcycle club – the first and only female motorcycle club in the country: the Mongolian Lady Riders. Modern nomads.

I made a short film about the motorcyclists and have photographs from the entire trip, but it takes thought and care as to how they might be used. My experience with the Dukha, for example. It was a nice experience, but parts still felt awkward, and we as artists or tourists always need to be careful as to how we present, and indeed to an extent, ‘exploit’ such encounters and topics for our own artistic ends.

I’m also working on a portfolio of analogue photographs of female characters in mythology, and in the gallery we are slowly getting back to exhibitions, readings and film screenings. Thanks to the pandemic, and the ever-changing situation, it is hard to plan things in advance. But in 2022 we hope to host some photography workshops and collaborations with different people from our neighbourhood in Berlin.

Galerie Arnarson & Sehmer, Berlin

In the Pines by Paul Scraton and Eymelt Sehmer, published by Influx Press