By: JP Robinson

Feb 22 Friday

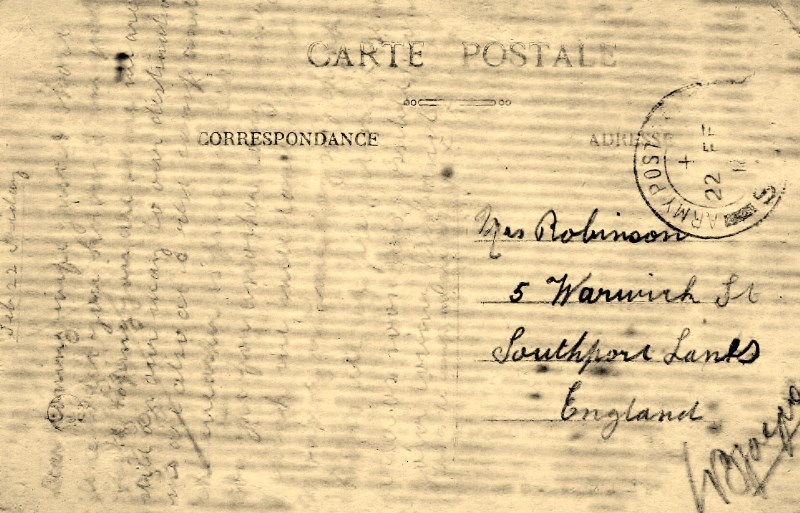

Dear loving wife just a short line to let you know… just… hoping you are… we are on our way to our destination. We are also at a rest camp and the weather is fine. … another long journey … we will … as soon as possible … your loving husband X X X This is the camp X X X

Most of the text on the postcard that James, my great-grandfather, sent to Lucy, my great-grandmother, is faded now, but the address and the censor’s counter-signature are still clear. Although he had no Scottish heritage, he was a private in the Liverpool Scottish, and he wore his battalion kilt as he wrote, from Le Preol, in northern France. There wasn’t much at Le Preol, aside from the well-established rest camp, with the corrugated iron buildings pictured on the postcard. Another Liverpool Scottish man remembered “a pretty little village set in low-lying wooded country close to the Aire-La Bassee Canal”, which “showed none of those jagged stumps of shell-riven trees that betoken counter-battery work”. The men didn’t stay for long. James wrote the card on a Friday, knowing they were leaving soon. On the Monday, they walked the two miles to the trenches, just as they had at the Somme and Ypres.

There were vast craters at the front line, around the ruined villages of Givenchy and Festubert. One crater, known as Red Dragon, was one hundred yards long and fifty feet deep. A soldier who relieved the Liverpool Scottish recalled that, as he arrived, “dead men lay about”. There were “bloated trench rats”, he said, and scared soldiers in need of rum. The communication trench “was sickeningly yielding underfoot with the bodies of the buried men. Here and there a leg or an arm protruded from the trench side”.

James’s life had been haunted by death. He was born in 1882, and was named after his six year old brother, who had died the year earlier. The family lived at 75 Cemetery Road, in Southport, Lancashire. Apart from his time in France, he lived all of his life within a hundred yards of the cemetery. There was a monument there, built when James was six, for the twenty seven men who’d died in the Great Lifeboat Disaster. Two of the dead were James’s cousins, who lived around the corner, on Boundary Street.

Following the disaster, James’s grandfather took over as coxswain of the new lifeboat. There was a second, less famous, lifeboat disaster ten years later; James’s grandfather, his father and an uncle drowned when they were working on the lifeboat moorings off the pier. James’s mother died sixteen months later, when he was eighteen. They were living at 28 Warwick Street then, perpendicular to Cemetery Road. James became a market porter, and then drove a bread van, before going to war. He was the first man in his family not to make his living on the fishing boats.

When he married Lucy, after a short stay at Matlock Road, parallel to Cemetery Road, they moved back to Warwick Street, to a two-bedroom end terrace at number 5. They had two children: Eliza, named for James’ mother, and James, my grandfather, born the year before war was declared. They could see the tower of the cemetery chapel from their back bedroom window. Lucy would have first read the postcard from Le Preol in their dark front room.

Lucy kept the postcard safe, of course. When she died, in 1979, thirty years after her husband, the children gathered the few pictures she’d had of him, the postcard, and James’ burial record. She’d been living in the nursing home that my grandmother ran, on the far side of the cemetery. One photograph had James in middle-age, standing proudly with his crown green bowling trophies in the back yard. Another had them both in front of their small bay window at Warwick Street. One, from the thirties, had them laughing as my grandfather acted up for the camera. There were two from a day out to Chester, with James in a smart suit. There were two others of him, from the war, in his Liverpool Scottish kilt. He posed formally in one, stiff-backed. In the other, he was with some friends beside a wooden hut, in the mud, smiling.

James had died in 1949, after his son had returned from fighting in Egypt in the Second World War. He was sixty seven, and had overdosed on barbiturates. Some in the family thought it was suicide. He was buried under a low headstone, in the cemetery behind his home, close to the lifeboat monument and the graves of the ninety seven men who had died in the Great War.