Place on paper: More joy of maps

/(Image: Bartholomew’s map of Merseyside, 1934)

We are delighted when something we do – whether in the journal or here on the blog – inspires a response. The following piece by Chris Hughes about a lifetime interest in maps and the depiction of place, was sent as a reaction to some of the stories and interviews with cartographers in Elsewhere No.04:

By Chris Hughes:

Want to know where you are? Driving to a place you don’t know? Mist comes down on the mountain? Check the map. Or the A to Z. Or that sketch on the back of an envelope.

But one way or another you need a map. That map might well be on your phone, tablet, satnav or a print out from your PC, but it’s still a map. However large, folded maps, books of town maps and even atlases still offer an accurate and detailed picture of a place that you can use for navigation, to learn about a place or simply to enjoy the experience of seeing a large picture of a location, and I have used and enjoyed – and even drawn – many different kinds of maps for many years.

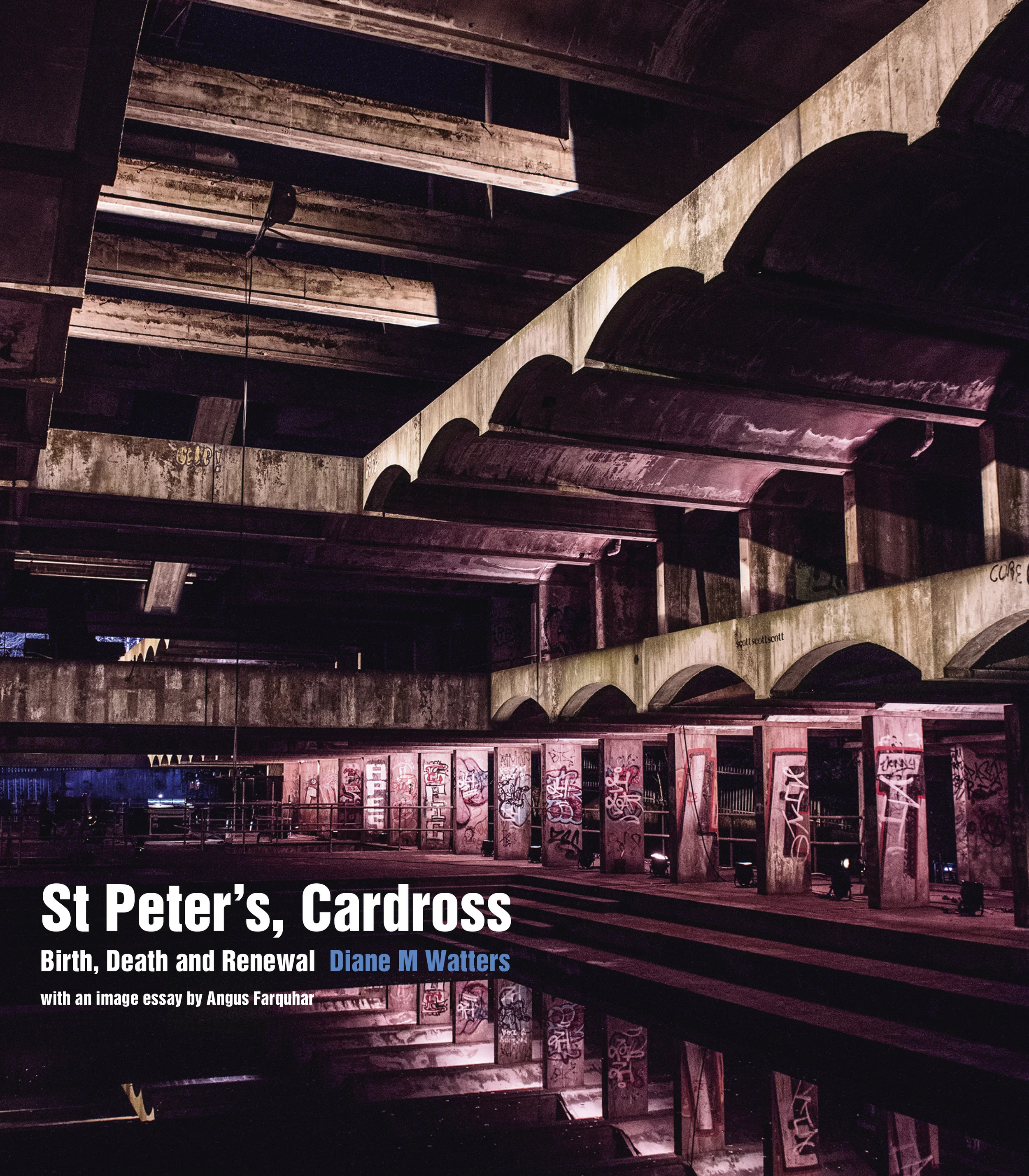

As a boy, I enjoyed visiting my Uncle Norman and looking at his Bartholomew maps, so beautifully coloured with tones of green, brown, blue and shaded to bring out the hills, mountains and valleys. Alfred Wainwright, the great guidebook writer and illustrator, loved his Bartholomew maps even though he based his own maps on the Ordnance Survey. And what about the OS? What a brilliant organisation, that has created the most comprehensive set of maps of the UK at a variety of scales and showing the minutest of details. They are still being constantly updated, these days using aerial photographs of the most incredible resolution to make the latest maps. Almost every walker that goes into the hills, everyone who has good sense at least, carries a map along with the compass, to ensure correct navigation and safety, even if they possess the latest GPS as insurance against the failures of batteries and satellite connections.

I went on to study geography and constantly drew small maps in notebooks, especially for the wretched exams, ending up with a degree dissertation containing many detailed maps of a small area of Snowdonia, all painstakingly drawn with my favourite Rotring pens, sitting in our flat in the depths of urban Bootle! The photographs included have faded badly but the maps are still vibrant.

Later in my working life I had to find my way to schools in unfamiliar towns and cities all over England, well before the satnav era. My collection of A to Zs grew steadily and never failed to help me find my way to the location.

Map collecting is obviously a big interest for many people and I could easily have joined them at one time; the beautifully illustrated map covers of the 1950s and 1960s are especially valued. I have a small number of cyclists maps which are fascinating in the details included. Sustrans guides to the cycleways of the UK are continuing the history of cycling maps in a modern fashion.

I have just enjoyed a first visit to the United State, driving through six of the great National Parks of California, Utah and Arizona and yes, maps were with us to help us find our way. Sure enough the satnav could not take us to every destination, but with the maps we got there in the end. I could not think about visiting a new place without having a map, still enjoy working out a new path and feel reassured that I have a collection of maps, guidebooks and A to Zs on the shelves to refer to when needed.

You can get your copy of Elsewhere No.04, which has a strong emphasis on maps and cartography, via our online shop.