The Fabric of Place: Yinka Shonibare's The British Library

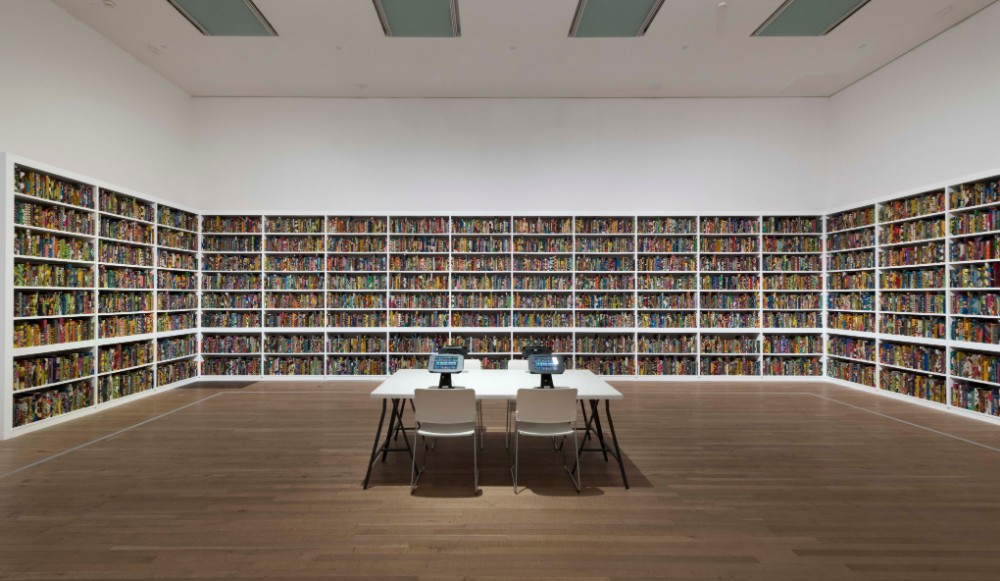

/The British Library, 2014, by Yinka Shonibare, Tate Modern 2019 © Yinka Shonibare. Photograph Oliver Cowling, Tate. Purchased with Art Fund support and funds provided by the Tate International Council, the Africa Acquisitions Committee, Wendy Fisher and THE EKARD COLLECTION, 2019

By Sara Bellini

It was 2014, during what ended up being my final months in England before leaving for good. In my attempts to deal with work-related stress I started taking day trips to escape central London, and it was thanks to two of these trips I came to know the work of Yinka Shonibare.

Without knowing it at the time, my first encounter with his art dated back to my very first week in the country in 2011. His work Nelson's Ship in a Bottle was on display on Trafalgar Square’s Fourth Plinth, with its colourful sails made of the artist's signature Dutch wax fabric. The fabric (and the meanings behind it) would be the detail that stuck with me during the years, while the photos I took got lost in my poorly managed digital memory.

Dutch wax fabric visually identifies West Africa, including Shonibare's parents' native Nigeria, where he also lived as a child before moving back to the UK to study. What I didn't know about this textile is how complex its ties with colonisation, globalisation and identity are.

Dutch wax fabric takes one of its names from the Dutch merchants that started mass-producing it in the late 19th century, when it was first introduced to Africa through naval commercial routes. Their model was batik, a wax-resist dyed cloth from Indonesia, a Dutch colony until 1949. The initial purpose of the merchants was to break into the batik market with cheaper fabrics, but they couldn't compete with the original hand-made prints. Meanwhile the African market was prospering, driven by ex members of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army in Indonesia who had returned to the Dutch Gold Coast in West Africa. Other European countries started making Dutch wax fabric and eventually local companies developed more African-inspired patterns. When African countries gained independence from their former oppressors after WWII, African wax print had interwoven its role into various African communities, especially in the West, enriched with local meanings and customs.

This is how we get to a British contemporary artist, born from Nigerian parents who had moved to the UK in post-colonial times. Shonibare explores all these themes in his works: (post-)colonialism, multiculturalism, history, identity.

The two exhibitions I saw when I was still living in London were at Royal Museums Greenwich and the installation The British Library at Brighton Museum. The British Library is a room lined up with bookcases where each book is covered in Dutch wax print and their spines carry the names of immigrants and children of immigrants that had made contributions to British culture. A computer was available to explore the library and find out about Zaha Hadid, Hans Holbein, Noel Gallagher and more famous and less famous names.

At the beginning of April 2019, Yinka Shonibare's work The British Library was purchased by Tate Modern. Another work from the same series, The African Library, is on display in the exhibition Trade Winds at the Norval Foundation in Cape Town until August 2019.