A city, best peeled thinly

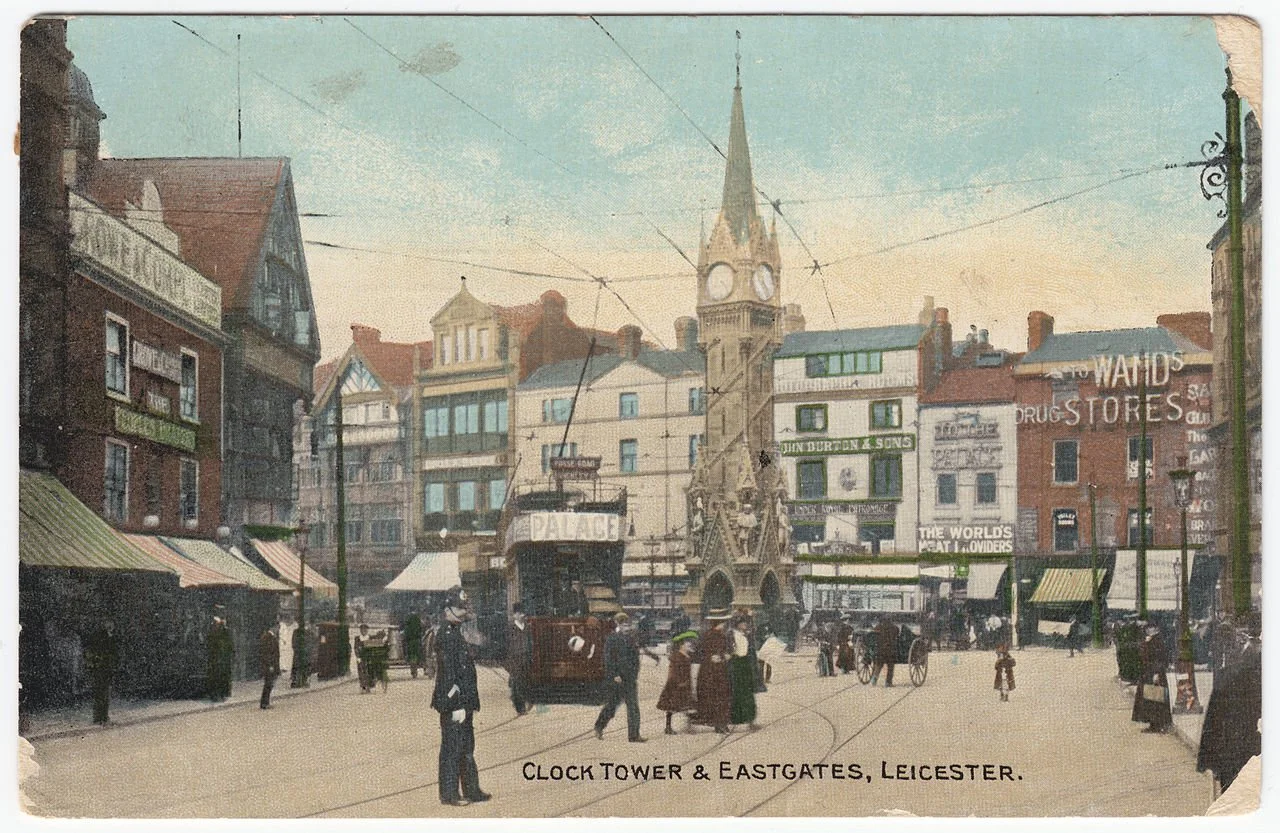

/A postcard of central Leicester, showing East Gates and the Haymarket Memorial Clock Tower. Wikimedia Commons

By Sharon Tyers

I come from a city of many layers - Leicester, sandwiched neatly into Middle- England where you can’t ever hear the sea. Now I live where you can’t fail to hear it, but my heart, my soul lies back in that industrial heartland. Peel it back carefully, and thinly, as mum did her Spanish onions on Sunday teatime and if you can avoid the tears, as she always did because she had no time for sensitivities, you will find gold there. Ancient gold - men, women and children, mostly unknown, mostly forgotten.

For its layers have exposed many a Roman remain, the odd King of England, a smattering of betrayed cardinals and more than its fair share of no-nonsense old sock linkers, one of them, my mother. She was a grafter, and followed the tradition set by her mother, grandmother and great grand mother of starting work at the hosiery factory at the age of twelve. Twelve- hour days, one for each year of your life, separated out the weak from the chaff, she was fond of saying.

The reason so many of them keep popping up, from between the layers, like yesterday’s lost socks which mum linked for forty years, is because they lie in shallow, thin sedimentary layers, patiently waiting their turn to make history. They’re happy to queue because queuing is one of the city’s treasured pastimes. If you’re from Leicester, you’re happy to queue. We queued with great pride for a 2lb pork pie in the market place on Christmas Eve, in Lewis’s at the broken biscuit counter and for the bus home from Newarke, where they laid Richard III’s broken body out on public display after the Battle of Bosworth. My grandma loved to queue and in 1947, one of Leicester’s notoriously bad winters, she waited in a very long one at 3am to buy coke from the only place you could get it at Aylestone Gas Works. She then carried the sooty sack on her back for two miles through a snow storm, made up the fire for my mum to dress by and then walked another mile with my mum, aged fifteen, to start work at the hosiery factory at 7am. At eighteen my mum walked from the same factory to queue up at the Leicester Palais, the new dance hall, and met my dad, home from the navy. Today, amongst the dilapidated rubble, which is all that is left of that iconic palace, you will find many a kirby grip and bun ring glittering amongst the layers - buried treasure from the dance floor, ready to tell its stories.

These layers of the past mingle and jostle with the present. We walk over the same footsteps trodden by our ancestors before us and try to do things a little better than they did – it’s called progress and that’s why they’re digging up Leicester market today. They want to build a new one whilst we all mourn the bulldozing of the old one. Damp cabbage leaves, bigger than our feet, and black as coal, unwashed spuds must make way for something a little more culturally refined, like enormous bowls of multi coloured olives and sizzling pans of paella, neither of which I remember being there in the 60s. Yet dig deeper through those layers of history and you’ll find they were there after all: a roman market place full of the exotic imports we yearn for today: bowls of figs, grapes, olives, hazelnuts, sloes, plums, blackberries and sorrel. We go forwards, not realising we are actually going backwards. We re -write the same page, rubbing out the past, pretend we’ve invented something new. Yet I can’t help but think the soul of the place is being permanently erased by the clean lines of progress and my aching heart yearns for the rough and tumble enjoyed by the everyman.

Inevitably, it’s not long till the digging stops at Leicester market because, yes, you’ve guessed it, popping up are those relics of the past and the archaeologists call a halt. It might be the grave of Cardinal Wolsey after all, who collapsed at the abbey nearby and so never made it to London for his beheading by Henry VIII. Unlike Richard’s, Wolsey’s bones haven’t yet been found but it didn’t stop them naming a sock factory after him. There’s fierce competition going on between the bigwigs as to who might find him first and whether the C for carrot on the old market trestle tables might in fact mean C for cardinal, as the R for Richard did in the car park. Perhaps it’s a more realistic goal to make a claim that the L marks the spot where Gary Lineker’s dad had his fruit and vegetable stall instead of just being L for lettuce, but it’s only an idea.

Of late, I’ve found myself reflecting on whether my home town is a memorial to the rich and famous or the ordinary worker and my question was answered on a Facebook site only this week. Where else? - I’d already tried the university that was only a poly in my day and they couldn’t answer my questions. But after I posted a picture of the statue of an ordinary hosiery worker, The Leicester Seamstress, who ironically sits on the corner of Hotel Street, one of the grandest streets in the city, when she herself lived in the Victorian slums, over 500 Leicester folk, young and old, popped up within minutes, wanting to share their love for her. Packed full of personal memories of their kin, they rushed forward to celebrate what she represented- the very ordinary, hard - working Leicester woman. They wanted to say she was their favourite statue, stand aside Richard III and Cardinal Wolsey, and share how much they missed the sock linkers, the overlockers, the steam pressers, the cutters and knitters who once made up their old hosiery town when it was known as the city that clothed the world. One told me of their grandma who died from an infected needle in one factory and another said her great grandmother was an out worker, staying up late at home seaming stockings as my own mum did after we had gone to bed. Her son would take the finished bundles of stockings at 5.30am to the factory gates and the money would allow him to buy bread, milk, tea and dripping for the family. Their words are full of romance and nostalgia for a bygone age and yet it is true to say the times they recall were also brutal. When your fingers stopped, so did the money, explained one woman about the piece work and might explain why my mum’s old hands are bent with arthritis.

My mum left Leicester and all that she knew and gave to the city in 2018, three years after catching the bus into Leicester to watch Richard III be re buried 200 yards from where he had quietly lay for five hundred years. She has no voice, only a howl at the indignity of her existence and lies bedridden in a nursing home on the North Wales coast where I now live. When she passes, I will take her back home to where she belongs, Leicester, and we will walk together over those layers of history and those pavements of gold.

Sharon Tyers is a retired English teacher and has published one novel in 2022 called “Linen and Rooks” set in Denbigh, North Wales, where she lives. She is a writer for the Baby Wolf newspaper, edited by Horatio Clare, where she also write articles about topical issues such as the need for better oratory skills being taught in UK schools. She also published in Little Toller Books’ “The Clearing”, and is currently writing the untold story of the wife of “The Mayor of Casterbridge”, Susan Henchard, after her husband sells her at Weydon Fair on Michaelmas day. It is the honour of Sharon’s lifetime to re-imagine the missing years in Hardy’s iconic novel.